2020 was — to borrow a phrase from a popular kid’s book — a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year. That means having to discuss a lot of tough subjects with our kids, and for parents, one of the year’s hardest jobs was trying to explain the state of the world in a way children can understand.

“We are living in challenging times,” says children’s book author Matt de la Peña — and kids are taking a lot of it in. “While you and I read the news, watch the news, listen to the news — our young children are watching and reading us, and so they’re not getting the whole picture,” he says.

De la Peña believes books can explore deep or tough subjects without hitting them head-on. “I don’t think the job of a picture book is to answer questions,” he says. “I think it’s just to explore interesting topics.”

Books should begin conversations, he explains: “Sometimes those are silly conversations, sometimes they’re educational conversations and sometimes, like now, they can be quite profound.”

De la Peña’s latest book, Milo Imagines the World, illustrated by Christian Robinson, is out in February. He offers several suggestions for books that can help young kids think about tough subjects.

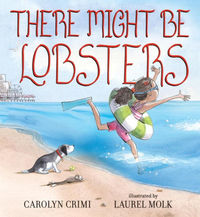

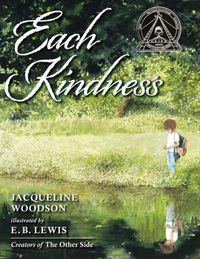

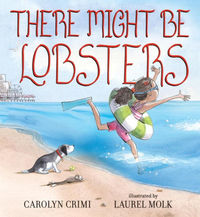

For A Child Experiencing Anxiety: There Might Be Lobsters by Carolyn Crimi, illustrated by Laurel Molk (for ages 3 to 7)

For A Child Experiencing Anxiety: There Might Be Lobsters by Carolyn Crimi, illustrated by Laurel Molk (for ages 3 to 7)

There Might Be Lobsters tells the story of Suki, a dog who is scared of the beach. The waves, the sand, the possible lobsters — it’s a lot for a little dog to worry about, and de la Peña says that kids living through these times will get that.

“I think so many kids right now can’t really identify why they’re anxious,” de la Peña says. “But there’s this feeling, there’s this darkness inside of them.”

While adults may try to examine and understand their anxiety, de la Peña says, “kids are experiencing it viscerally.”

Eleanor, Sukie’s human, does her best to ease her dog’s fears. But it’s only when Sukie’s stuffed toy, Chunka Munka, gets taken by a wave that the little dog finds the courage to get into the ocean.

“What I love about this book is we see a dog who is pushed out of her comfort zone,” de la Peña says. “It’s great to read today with kids because so many of us are forced out of our comfort zones.”

The book touches on difficult themes — fear, anxiety, lack of control — but in a manageable way. “You can have a young reader who doesn’t really consciously put their finger on the anxiety that’s being explored — they just like the lobster story,” says de la Peña. “But viscerally, I’m sure they’re getting something.”

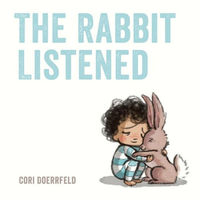

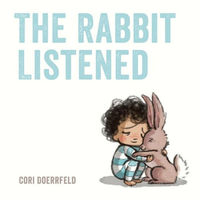

For A Child Who Is Upset: The Rabbit Listened by Cori Doerrfeld (for ages 3 to 5)

For A Child Who Is Upset: The Rabbit Listened by Cori Doerrfeld (for ages 3 to 5)

Even adults have trouble knowing how best to support someone who is experiencing a loss. This is a story that reminds kids — and their grown-ups — that sometimes the best thing to do is to just be present and bear witness.

Taylor is so disappointed when his amazing block tower comes tumbling down. Several animal friends stop by to help: The chicken wants to talk about it; the hyena wants to laugh about it; the elephant wants to rebuild it; the ostrich wants to hide from it. But none of that helps Taylor feel better.

Finally, “rabbit comes in quietly and just sits with Taylor, allowing the child to process the small tragedy organically,” de la Peña says. He says this picture book offers helpful guidance in “how to best support a young person who is upset.”

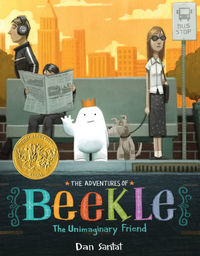

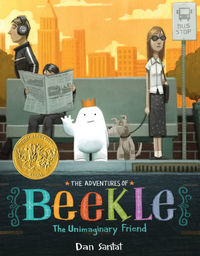

For A Child Searching For Their Place In The World: The Adventures of Beekle by Dan Santat (for ages 4 to 8)

For A Child Searching For Their Place In The World: The Adventures of Beekle by Dan Santat (for ages 4 to 8)

An imaginary friend is born on an imaginary island — all he has to do is wait to be chosen by a real child. But after nights and nights of waiting he decides he must fight for his own fate.

“He takes matters into his own hands and builds a ship and sails into the real world on his own,” de la Peña says.

After a long journey he finds himself in a busy city where at last he meets a little girl who “felt just right.” She names him Beekle, and they take off on “unimaginable” adventures.

“I love the way this book explores the psychology of how a child can marry the dreamy world of childhood imagination with the real world and human friendships,” de la Peña says.

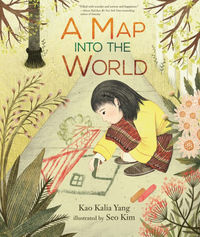

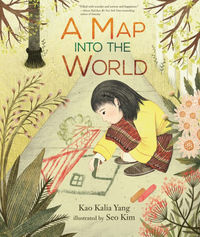

For A Child Thinking About Death: A Map into the World by Kao Kalia Yang, illustrated by Seo Kim (for ages 5 to 9)

For A Child Thinking About Death: A Map into the World by Kao Kalia Yang, illustrated by Seo Kim (for ages 5 to 9)

Many children have lost a neighbor, a friend or a family member to COVID-19. De la Peña says Kao Kalia Yang’s A Map into the World is a good way to broach this painful subject.

It’s the story of a young girl who moves in across the street from an elderly couple. When the wife dies, the girl “can’t quite access what it means, but it weighs on her and it weighs on the entire street,” de la Peña says.

So she takes her bucket of chalk and draws her grieving neighbor “a map into the world” on the sidewalk. “This is a girl trying to process things she doesn’t fully comprehend … but she has this visceral instinct to go and do something,” de la Peña says.

Grief and loss feel heavy, but they can be hard for kids to conceptualize — especially now. “We can’t see the person who’s sick in the hospital … we can’t go to funerals,” de la Peña says. “So it’s just information that you’re downloading and you don’t know how to process.”

A book like this, he says, can help bridge that gap.

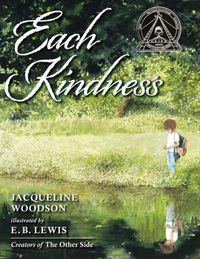

For A Child Struggling To Be Kind: Each Kindness by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by E.B. Lewis (for ages 5 to 8)

For A Child Struggling To Be Kind: Each Kindness by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by E.B. Lewis (for ages 5 to 8)

This is one of de la Peña’s “all-time favorite” picture books.

Maya, a new girl at school, wears ragged clothes and has trouble making friends. Chloe won’t even return her smile.

“By the time Chloe learns a lesson about the power of kindness, she’s missed her chance to be kind to Maya who has moved away,” de la Peña explains.

Missed opportunity and regret aren’t common themes in children’s literature. “I so admire this book for resisting the happy ending and allowing Chloe’s story to end on regret,” de la Peña says. “It’s a powerful experience for young readers.”

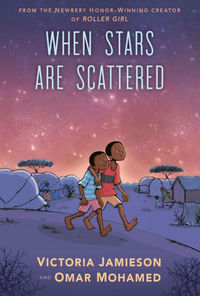

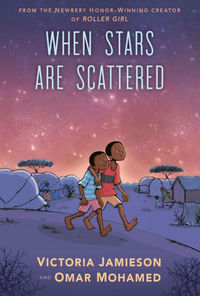

For A Child Feeling Stuck: When Stars Are Scattered by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed, illustrated by Victoria Jamieson and Iman Geddy (for ages 9 to 12)

For A Child Feeling Stuck: When Stars Are Scattered by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed, illustrated by Victoria Jamieson and Iman Geddy (for ages 9 to 12)

Many kids may feel stuck at home — away from friends, relatives and school — during lockdown. So de la Peña suggests a graphic novel that tells the true story of Omar Mohamed, a Somai refugee who grew up in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya.

“There’s a line in this book that kind of hits today’s climate head on,” de la Peña says, when Mohamed talks about just waiting for his life to begin.

“I feel like so many of us are feeling the same way and so are our children,” de la Peña says.

Graphic novels and picture books can be a great way to explore tough subjects with kids who aren’t comfortable reading yet.

“Sometimes we can have visual learning happening alongside textual learning …” de la Peña says. “We can read the faces of the characters.”

Parents should remember that there are many different ways for a child to read. “I think it’s important not to put too much pressure on children to read at our pace, but to read at their own pace,” de la Peña says. “That’s what I love about picture books. You can enter the story via text or via illustration and ultimately, you know, kids are going to get to both.”

Acknowledging When Life Is Scary

Acknowledging When Life Is Scary

De la Peña’s 2018 book, Love, illustrated by Loren Long, grapples with tough subjects, too — in one illustration a child hides under a piano while his parents have an argument. In another, a child walks in as his family is taking in upsetting news on the television. De la Peña couches these fearful moments in the context of love and protection.

“I wanted a story that I could read to my daughter before bed that would make her feel good, considering that the news wasn’t always so positive,” de la Peña says. He says there are great books that are purely positive and reassuring, but he found that this sort of book didn’t feel true to his experience as a parent.

“I had to at least acknowledge adversity because every child is going to be confronted with adversities throughout their life,” he says.

For parents who are worried about discussing tough subjects with their kids, perhaps it will be helpful to remember that even award-winning children’s book authors feel daunted by this responsibility: “I’m afraid of those moments as a parent, too,” de la Peña says.

This article originally appeared here.

Boston Tutoring Services